The treatment landscape is rapidly changing in multiple cancers, including hepatic and biliary tract cancers, with the introduction of targeted and immunotherapy. It has been exciting the last couple of years in advanced biliary tract cancers with rapidly evolving novel treatments.

Biliary tract cancers

Biliary tract cancers are typically diagnosed in advanced stages and associated with a poor prognosis. The standard of care has essentially stayed the same for more than a decade. Based on data from the ABC-02 trial1 in 2010, the combination of gemcitabine with cisplatin has become the standard of care for all patients with advanced biliary tract cancers in the first-line setting.

Most recently the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Durvalumab, the anti-PD-L1 antibody, in combination with gemcitabine and Cisplatin for adult patients with locally advanced or metastatic biliary tract cancer based on the TOPAZ-1 trial.2 It showed a Durvalumab/chemotherapy combination improved objective response rate, progression-free survival, and median overall survival across a broad population of patients and subgroups. The overall survival data increased over time, thereby suggesting that we may be seeing prolonged immune responses.

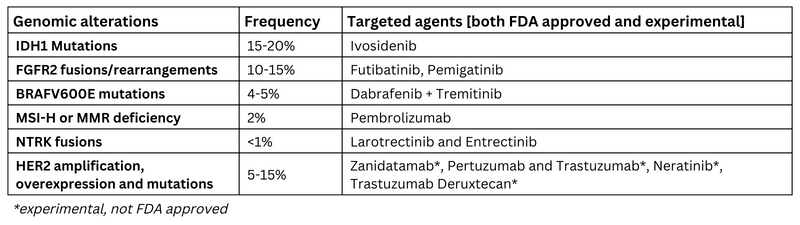

Next-generation sequencing is currently the standard of care in advanced biliary tract cancer with a multitude of options available after the progression of chemotherapy and immunotherapy as summarized below in table 1.3,4 Further clinical studies are ongoing to determine targeted therapies vs. standard of care in first-line management of metastatic biliary tract cancer with genomic alterations.

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide5, with major global risk factors being hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV). HBV vaccination, as well as new and effective treatments for chronic infections for both HBV and HCV, likely leads to a decline in the rates of viral etiology of HCC. Given the increasing prevalence of obesity, type II diabetes, metabolic syndrome and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, they might contribute to major causes of HCC globally.6

Localized disease can be managed with surgical resection, liver transplant, local ablative therapies, arterial-directed therapies, and radiation treatment. The systemic treatment landscape of HCC has significantly changed over the last couple of years for advanced disease. Sorafenib was the only FDA-approved drug for HCC from 2007 until 2017, when we received a multitude of further approvals both in the first-line and further line of management.

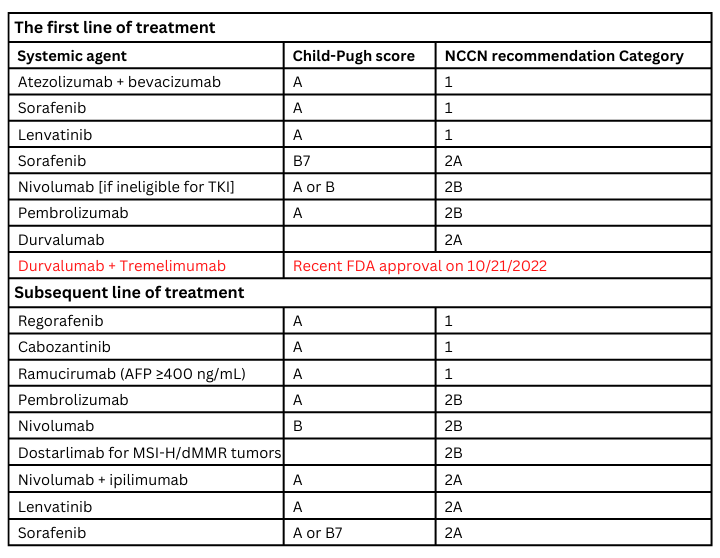

Systemic treatment options are summarized in table 2.7 More data evolving on etiology – viral vs. no viral [Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis vs other] and implications on treatments.8 We have an unmet need for better biomarkers to choose treatments, more data on etiology-directed treatment, integration of local and systemic therapies, and treatment options for patients with Child-Pugh score B with good performance status. Additionally, whether child-pugh score vs ALBI [albumin-bilirubin] vs a modified version of ALBI acts as a better index of hepatic functional reserve needs to be determined.9

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a relatively uncommon cancer, with approximately 62,000 new diagnoses in 2022 in the U.S.10 The incidence of PDAC is increasing by 1.1% per year globally. Five-year survival rates are dismal at 11% in general and 3% for metastatic PDAC.

Risk factors for developing pancreatic cancer include tobacco use, obesity, diabetes, chronic pancreatitis and exposure to chemicals, and familial syndromes.10 PDAC is diagnosed at advanced stages and no screening is available for the general population. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommends screening for individuals at increased risk of pancreatic cancer because of genetic susceptibility annually with EUS (endoscopic ultrasound), MRCP (magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography), or a combination of these modalities.11 Many patients have locally advanced and metastatic disease at presentation.

Localized pancreas cancer can be classified into resectable, borderline resectable and unresectable disease based on the degree of arterial and venous involvement by the tumor. About 10%-15% of patients at presentation have resectable disease, for which surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with FOLFIRINOX (fluorouracil, irinotecan, leucovorin, oxaliplatin) represents a standard approach with a median overall survival of 54 months.

For resectable and borderline resectable disease, neoadjuvant systemic therapy, with or without radiation, followed by surgery is an option in patients with good response. For patients with locally advanced and unresectable disease due to extensive vascular involvement, systemic therapy followed by radiation is an option for definitive locoregional disease control. For patients with locally advanced and metastatic PDAC, multiagent chemotherapy regimens, including FOLFIRINOX, gemcitabine/Nab-paclitaxel, and nanoliposomal irinotecan/fluorouracil, all have a survival benefit. For patients who have a BRCA pathogenic germline variant [5-7%] with metastatic PDAC, olaparib, a poly (adenosine diphosphate [ADB]-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, is a maintenance option that improves progression-free survival following initial platinum-based therapy.12

A recent publication showed a patient with progressive metastatic pancreatic cancer treated with a single infusion of T-cell receptor gene therapy targeting mutant KRAS G12D had an excellent response.13 Multidisciplinary management, comprehensive germline analysis, consideration of clinical trials and supportive care are recommended for patients with pancreatic cancer.

References:

- Valle J., Wasan H., Palmer D.H., et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010; 362(14):1273–1281.

- Oh DY, Ruth He A, Qin S, Chen LT, Okusaka T, Vogel A, Kim JW, Suksombooncharoen T, Ah Lee M, Kitano M, Burris H. Durvalumab plus Gemcitabine and Cisplatin in Advanced Biliary Tract Cancer. NEJM Evidence. 2022 Jun 1:EVIDoa2200015.

- Lamarca A, Edeline J, Goyal L. How I treat biliary tract cancer. ESMO Open. 2022 Feb; 7(1):100378. Doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100378. Epub 2022 Jan 13. PMID: 35032765; PMCID: PMC8762076.

- Valle JW, Kelley RK, Nervi B, Oh DY, Zhu AX. Biliary tract cancer. Lancet. 2021 Jan 30; 397(10272):428-444. Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00153-7. PMID: 33516341.

- https://www.cancer.org/cancer/liver-cancer/about/what-is-key-statistics.html accessed on 10/10/2022.

- McGlynn KA, Petrick JL, El‐Serag HB. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2021 Jan; 73:4-13.

- https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/hepatobiliary.pdf, NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2022 Hepatocellular Carcinoma accessed on 10/10/2022.

- Gardini AC, Rimini M. ESMO World Congress on Gastrointestinal Cancer 2022;Abstract SO-14.

- Kudo M. Newly Developed Modified ALBI Grade Shows Better Prognostic and Predictive Value for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2021 Dec 8; 11(1):1-8.

- https://www.cancer.org/cancer/pancreatic-cancer/about/key-statistics.html accessed on 10/12/2022.

- https://www.asge.org/docs/default-source/about-asge/piis001651072101871x.pdf?sfvrsn=7d0f665c_1 accessed on 10/12/2022.

- Park W, Chawla A, O'Reilly EM. Pancreatic Cancer: A Review. JAMA. 2021 Sep 7;326(9):851-862. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.13027. Erratum in: JAMA. 2021 Nov 23;326(20):2081. PMID: 34547082; PMCID: PMC9363152.

- Leidner R, Sanjuan Silva N, Huang H, Sprott D, Zheng C, Shih YP, Leung A, Payne R, Sutcliffe K, Cramer J, Rosenberg SA, Fox BA, Urba WJ, Tran E. Neoantigen T-Cell Receptor Gene Therapy in Pancreatic Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022 Jun 2;386(22):2112-2119.